SAN FRANCISCO – Late in 2023, Robin Davis flew from her home in the Pacific Northwest to spend one weekend in New York City – and she planned to make the most of it.

She would meet up with a dear friend for dinner, then beeline to a three-story nightclub on the Lower East Side for drinks and dancing at an ’80s-themed party. Then, they would catch a ride to a boutique hotel in SoHo, where they would trade stories and sleep in. It had all the makings of a perfect New York night – until, Davis said, a thief posing as a club employee drugged her, gleaned her iPhone’s passcode and ripped it from her hands as she was getting into an Uber.

As if the shopping spree the thief went on with her saved credit cards wasn’t bad enough, Davis has never regained access to the crucial files – contacts, photos from her wedding, data related to work “and other essential information” – associated with her Apple account. That’s not just because of the people who stole her phone. It’s also because Apple won’t give it back.

“As a career sales executive this is a disaster of life-changing proportions,” she wrote in a letter to Apple chief operating officer Jeff Williams.

Apple, one of the most valuable companies in the world, with a market capitalization of close to $3 trillion, says it has an unwavering commitment to protecting users’ privacy and data, a stance it has stuck to even in the face of pressure from law enforcement. But some people who have had their iPhones stolen are discovering that Apple’s own security tools – meant to protect them – are sometimes being used against them. When iPhones are stolen, savvy thieves can lock owners out of their Apple accounts, making it difficult to reclaim precious photos and files. Now, a court case in California is giving some of these victims hope for retrieving their digital lives.

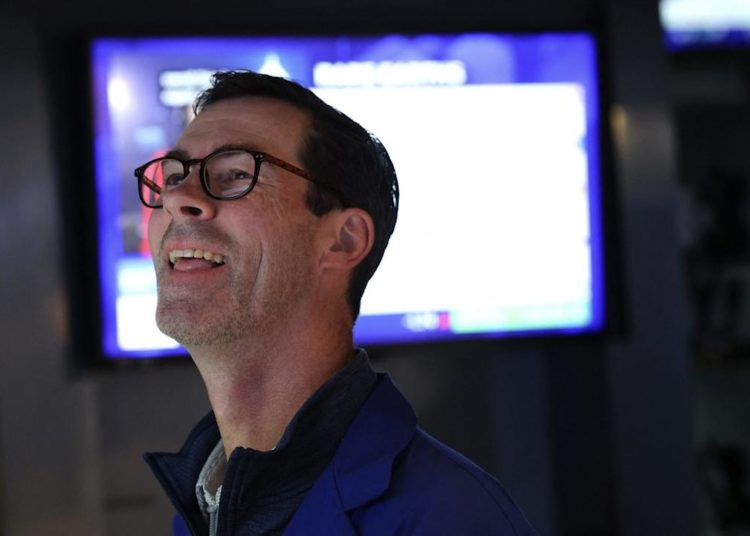

Michael Mathews, 53, is suing Apple, seeking access to 2 terabytes of data that made up his “entire digital life, including that of his family,” plus at least $5 million in damages, according to a January filing with the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

His iPhone was stolen weeks after Davis’s, in Scottsdale, Arizona, where pickpockets targeted the Minnesota tech executive and took off with his phone. He lost access to his photos, music, tax returns and research related to his work, according to court documents. His tech consulting firm had to shut down entirely, he claims in the lawsuit.

“Even though Mathews is able to provide substantial and unquestionable evidence that the accounts and the data in his Apple accounts are his, Apple nevertheless refuses to reset the Recovery Key or allow Mathews access to his accounts and data,” the complaint says. “In so doing, Apple perpetuates and aids the hackers in their criminal activity.”

Apple did not comment on Mathews’s legal case. “We sympathize with people who have had this experience and we take all attacks on our users very seriously, no matter how rare,” Apple said in a statement to The Washington Post.

“What’s indefensible is Apple holding on to data that they don’t own,” K. Jon Breyer, Mathews’s lawyer, said in an interview. “That’s a question Apple continues to refuse to answer. Under what basis do you get to keep your users’ data and not return it?”

For now, the wait for a remedy goes on. Breyer said the case is just entering the discovery phase, a process of pretrial evidence-gathering he expects to last at least six to eight months.

– – –

Locked down, locked out

iPhones are high-value targets, and thieves have learned they can extract more value from one if they learn their victims’ passcodes – like they did with Davis.

Once they have unlocked the stolen iPhone, the next step is often to change the password tied to a user’s Apple ID, making it harder to locate. And if a thief is thorough, they may create a “recovery key”: a random, 28-character code that is meant to help people regain control of their Apple account in case others take over.

Creating a recovery key disables the company’s usual account recovery process. The problem: It’s trivial for a thief to create a recovery key – or replace one you already made – if they know the person’s passcode. Once an iPhone has a new recovery key, regardless of who made it, Apple says “you’ll be locked out of your account permanently.”

“What we’ve learned is that Apple didn’t have a deep consideration over the threat model of someone having physical access to your device,” said Thorin Klosowski, a privacy activist at the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Once someone is locked out, all that account data – photos, notes, voice memos and more – live on, encrypted in the cloud. In some cases, Apple holds a copy of the keys needed to decrypt those files, just in case.

There’s one exception: If a user or thief has turned on a feature called Advanced Data Protection, all of that data is fully locked down and not even Apple can access it. But in cases where that advanced encryption isn’t being used – like Mathews’s – Apple isn’t hamstrung by technical limitations; it’s choosing not to return people’s data, experts allege.

Apple has “never expressed to us that they are unable to give the information back,” Breyer said.

Not all thieves go this far, and they may settle for changing the Apple account’s password, but Apple’s standard account recovery system can’t always help.

The company recommends that, during the recovery process, victims turn off all other devices tied to that Apple account. If the account is being used – even by thieves – the account recovery request “will be canceled automatically,” the company says.

For its part, Apple says it works “tirelessly every day to protect our users’ accounts and data, and to introduce additional protections like Stolen Device Protection, which helps protect your accounts and personal information in case your iPhone is ever stolen.”

Stolen Device Protection makes it harder for thieves to gain entry by requiring a Face ID or Touch ID scan to access passwords and credit cards, and delaying Apple account password changes.

But many users don’t know it exists. Stolen Device Protection was built into iOS and released in January 2024, but it is not enabled by default and isn’t always highlighted during the iPhone’s setup process.

Unless you take the right precautions, a dedicated thief can easily lock users out of their Apple accounts – but some security experts say figuring out how to restore those accounts is a solvable problem.

“You do have to provide a variety of information to sign up for an Apple account, and people could be required to provide things like police reports to show that they reported their phones stolen,” said Lorrie Cranor, director of Carnegie Mellon University’s CyLab Security and Privacy Institute. “I find it odd that Apple is fighting this without explaining their rationale.”

– – –

Last hope

For other victims, Mathews’s lawsuit is a rallying cry. Breyer said his firm has picked up 10 new clients with similar complaints.

Other victims hadn’t heard of the case, but now they’re hoping it will force Apple to take action.

“These situations happen,” said Eli Munk, a 30-year-old accountant from New York City whose iPhone was stolen while he was celebrating a friend’s birthday. Apple “can figure out a way to fix it.”

The thieves quickly started spending, and while many fraudulent charges were reversed, hundreds of dollars stored in Munk’s sports betting accounts were never recovered. More painful, he said, was the loss of years of photos – images that chronicled his evolution from high school kid to big-city professional – because he was locked out with a recovery key. He has since switched to a Google Pixel phone.

Apple “didn’t even care, it seemed. That was the hardest part,” said Munk.

Apple declined to comment on Munk’s case.

The lawsuit’s new supporters also include those who typically take their digital privacy seriously.

Max Gehman, 31, had set up a recovery key but lost the slip of paper the code was written on. Last October, he gave his iPhone to a group of people – new friends, he thought – in Austin to help them navigate back to his home. But those seemingly friendly folks weren’t just using Google Maps; they were draining his bank account.

Now, he just wants his Apple account back.

“I hope [Mathews] wins, and gets more money,” Gehman said.

As for Davis, she swore off Apple products after her ordeal. She said Apple’s inability to return her files, sitting securely in the cloud, only “revictimizes” people like her. But Mathews’s lawsuit offers the potential for closure.

Her sense of powerlessness has since given way to something else: a desire to help.

“I will fly anywhere to be part of anything that can change this system,” she said.

Related Content

Freedom Riders faced a mob at this bus station. DOGE wanted to sell it.

The Abrego García case: A timeline and assessment of key documents

Trump brushes aside courts’ attempts to limit his power

The post Thieves took their iPhones. Apple won’t give their digital lives back. appeared first on Washington Post.