Trump abruptly fires Librarian of Congress

WASHINGTON—President Donald Trump fired the Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden, on Thursday, according to a copy of her termination email...

FDA issues warning against tianeptine use, also called ‘gas station heroin’

This article discusses suicidal ideation. If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call...

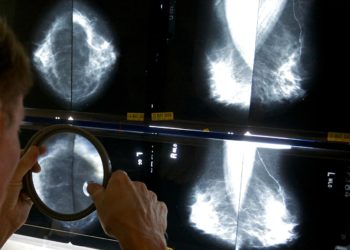

Cancer before age 50 is increasing. A new study looks at which types

Cancer before age 50 is rare, but increasing, in the United States and researchers want to know why.A new government...

Autopsy suggests South Carolina botched firing squad execution

A South Carolina firing squad botched the execution of Mikal Mahdi last month, with shooters missing the target area on...

Parkinson’s disease prevention may ‘begin at the dinner table’

Eating about a dozen servings of ultraprocessed food each day could more than double your risk of developing Parkinson’s disease,...

Detroit Three automakers blast Trump UK trade deal

By David Shepardson and Kalea Hall WASHINGTON/DETROIT (Reuters) -A group representing General Motors, Ford and Stellantis blasted President Donald Trump's...

‘Like the Cubs winning the World Series’

As white smoke billowed from the Vatican in Rome, yellow papal flags whipped in the crisp Lake Michigan breeze in...

What’s in a name? Why the new pope chose to be Leo XIV

Why did the first American to be elected pope, leader of the world's 1.4 billion Roman Catholics, choose Leo for...

Charlize Theron Revives Her Netflix Action Franchise and Battles a Lost-Long Immortal

Netflix has released the first trailer for “The Old Guard 2,” which sees the return of franchise star Charlize Theron...

Leo is America’s first pope. His worldview appears at odds with ‘America First.’

When the late Pope Francis challenged Donald Trump on immigration, climate change and poverty during the president’s first term, the...