Tesla robotaxi incidents spark confusion and concerns in Austin

Two weeks into Tesla’s robotaxi prototype rollout on the streets of Austin, Texas, a string of viral videos showing apparent...

Desperate search for missing girls from summer camp after Texas floods kill at least 24

KERRVILLE, Texas (AP) — At least 24 people were killed and a frantic search continued overnight for many others missing...

Unusual Social Security email touts Trump bill. Here’s what to know.

Social Security beneficiaries are accustomed to getting occasional emails from the program about matters like a benefits statement, but many...

3 mayors arrested in southern Turkey as part of crackdown on opposition

ISTANBUL (AP) — The mayors of three major cities in southern Turkey were arrested Saturday, state-run media reported, joining a...

Most Wanted’ Star Was 56

Actor Julian McMahon, known for his starring roles in Nip/Tuck, Charmed, FBI: Most Wanted and the 2000s Fantastic Four movies,...

Drone “narco sub” — equipped with Starlink antenna — seized for first time

The Colombian navy on Wednesday announced its first seizure of an unmanned "narco sub" equipped with a Starlink antenna off...

AI is making everyone on dating apps sound charming. What could go wrong?

Richard Wilson felt like he had struck gold: The 31-year-old met someone on a dating app who wanted to exchange...

China tells EU it can’t accept Russia losing its war against Ukraine, official says

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told the European Union’s top diplomat that Beijing can’t accept Russia losing its war against...

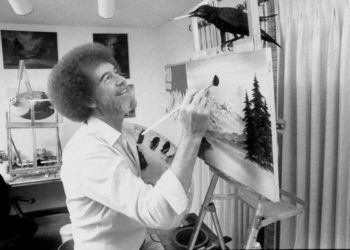

What to Know About the Late Painter’s Sudden Passing

NEED TO KNOWBob Ross died on July 4, 1995, a year after his series, The Joy of Painting, endedThe artist...

Trump signs megabill that slashes taxes, Medicaid while boosting national debt

President Donald Trump capped the whirlwind opening stretch of his second term with a Fourth of July signing ceremony for...