What to Know About the New COVID-19 Variant XFG

Credit - Getty ImagesWith summer travel at an all-time high, new COVID-19 variants are brewing. Officials at the World Health...

Debate erupts over role job cuts played in weather forecasts ahead of deadly Texas floods

WASHINGTON (AP) — Former federal officials and outside experts have warned for months that President Donald Trump’s deep staffing cuts...

Passengers will no longer have to take their shoes off at the airport

Nearly 20 years after airline passengers were first required to remove their shoes for security, the policy is being phased...

Netanyahu plays into Trump’s hopes for Middle East peace — and nominates him for a Nobel Prize

When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu arrived at the White House Monday for dinner, he came bearing what has become the...

Epstein ‘client list’ doesn’t exist, Justice Department says, walking back theory Bondi had promoted

WASHINGTON (AP) — Jeffrey Epstein did not maintain a “client list,” the Justice Department acknowledged Monday as it said no...

He saw her in Yellowstone and thought ‘I’m going to marry that girl.’ And he did

The moment Andrew McGowan and Shallen Yu met eyes through a storefront window, it felt like something passed between them....

New Memo Rebuts Epstein Conspiracies: What to Know

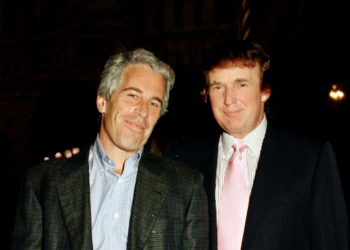

Jeffrey Epstein, left, and Donald Trump together at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Fla., in 1997. Credit - Davidoff Studios—Getty ImagesThe...

Doctors’ groups sue Kennedy over Covid shot changes for kids, pregnant people

A coalition of doctors’ groups led by the American Academy of Pediatrics filed a lawsuit Monday against Health Secretary Robert...

‘I was shunned, dumped, cancelled – however you want to define it’

The first time I see Johnny Depp, he is holed up in a caravan on a Budapest backstreet. Smoking a...

Trump to put 25% tariffs on Japan and South Korea

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump on Monday placed a 25% tax on goods imported from Japan and South Korea,...