Trump files libel lawsuit against Wall Street Journal over Jeffrey Epstein story

President Donald Trump has filed a libel lawsuit against the Wall Street Journal, Rupert Murdoch and others over the Thursday...

17-year-old charged with murder in paddleboarder’s killing at a pond in rural Maine

PORTLAND, Maine (AP) — Authorities in Maine said Friday they have charged a 17-year-old with murder in the death of...

Unknown illness sickens 140 people aboard Royal Caribbean cruise

Over 140 passengers and crew members aboard a Royal Caribbean International ship have been sickened by an unidentified illness, the...

Witnesses to Felix Baumgartner’s fatal paragliding crash heard large boom as it spun to the ground

PORTO SANT'ELIPIDO, Italy (AP) — Beachgoers knew something was wrong when they heard a loud boom ring out as a...

Trump appointees pushed more marble in Fed building renovation White House now attacks

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump has looked to the marble finishes and hefty price tag of the Federal Reserve...

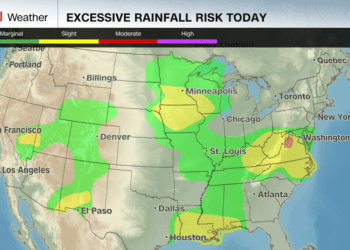

Heavy rain threatens flash flooding for millions across much of the US

Tens of millions of people are at risk of dangerous flash floods in pockets of nearly every region of the...

Digging through sand, mud, debris and silt. Why the search for the missing in Texas may take months

Sixty miles of river. Murky waters, thick mud and seemingly insurmountable piles of debris.Painstaking recovery efforts are still underway for...

Trump Celebrates Congress Pulling $1.1 Billion in Funding From ‘Atrocious’ NPR and PBS: ‘This Is Big!’

President Donald Trump took a victory lap after Congress formally passed his measure to claw back $9 billion in previously...

Public broadcasters say GOP funding cuts could be ‘devastating’ to local media and make Americans less safe

When a magnitude-7.3 earthquake struck off southern Alaska on Wednesday, officials were concerned about a potential tsunami. It was local...

Cost of Obamacare expected to soar as subsidies expire and insurers hike premiums

People who get health insurance through the Affordable Care Act could soon see their monthly premiums sharply increase as subsidies...