Supreme Court allows Trump to lay off nearly 1,400 Education Department employees

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court is allowing President Donald Trump to put his plan to dismantle the Education Department...

Justin Baldoni Responds to Blake Lively’s Motion Requesting Judge Issue a Protective Order Ahead of Her Deposition

NEED TO KNOWJustin Baldoni's legal team has issued a response to Blake Lively's request for a judicial protective order in...

Bongino still in limbo as Trump fumes and JD Vance seeks to play mediator, sources say

Several of President Donald Trump’s top officials went to work on Monday with a key question unanswered: would Dan Bongino...

Who will win the Senate in the midterms? The answers to these 5 questions could tell you.

The battle for the Senate won’t be decided for another year and a half. But the key questions that will...

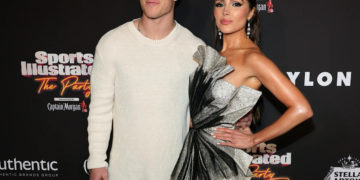

Brody Jenner marries pro surfer Tia Blanco in intimate Malibu ceremony

Brody Jenner and Tia Blanco have officially tied the knot.The former star of The Hills and member of the famous...

A British aristocrat and her boyfriend are convicted of killing their newborn

LONDON (AP) — A British aristocrat who went on the run with her boyfriend and their newborn daughter in 2023...

Trump threatens 100% tariffs on Russia

President Donald Trump is scheduled to welcome NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte to the White House on Monday, a day after...

Trump Risks Losing Supporters Over Epstein Fallout

President Donald Trump walks on the South Lawn of the White House on July 13, 2025. Credit - Allison Robbert—AFP/Getty...

Wildfire destroys historic Grand Canyon Lodge, North Rim closes for the season

The Grand Canyon Lodge was one of dozens of structures destroyed in a fast-moving wildfire in Arizona over the weekend,...

How “The Gilded Age” Season 3 Opens the Door for a Potential Crossover with “Downton Abbey” (Exclusive)

Warning: Some spoilers for The Gilded Age season 3, episode four NEED TO KNOWSeason 3 of The Gilded Age may have...