The ‘R-word,’ embraced by Joe Rogan and Elon Musk, inches back into the mainstream

In a recent episode of his highly influential podcast, Joe Rogan declared what he sees as the latest triumph in...

A 2012 video shows comments from new pope that disappoint LGBTQ activists

VATICAN CITY (AP) — Pope Leo XIV, in remarks in 2012 when he was the Augustinian prior general in Chicago,...

Former president’s son implicated in safari murder of British woman

The son of the former Kenyan president has been implicated in the murder of a young British woman in newly...

Hunger has been weaponised as people in Gaza face mass starvation

Re your editorial (The Guardian view on Israel’s aid blockade of Gaza: hunger as a weapon of war, 4 May),...

Rose McGowan Has Found ‘So Much Joy’ 5 Years After Leaving Hollywood for Mexico

Rose McGowan left Hollywood for Mexico in 2020 and hasn't looked backSpeaking on a Charmed panel at 90s Con 2025,...

Jury selection for sex trafficking trial of Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs is pushed to next week

NEW YORK (AP) — The final stage of jury selection for the racketeering and sex trafficking trial of hip-hop mogul...

Bill Gates says Elon Musk’s DOGE is ‘killing’ poor children

Bill Gates is holding Elon Musk responsible for the preventable deaths of the world’s poorest children, as a result of...

UK political opinion poll tracker

Labour have fallen a long way since their landslide victory last summer.Testament to just how serious the challenge from Reform...

Trump, Kennedy defend new surgeon general pick amid MAGA backlash

By Ahmed Aboulenein and Andrea ShalalWASHINGTON (Reuters) -U.S. President Donald Trump and his health chief Robert F. Kennedy Jr. are...

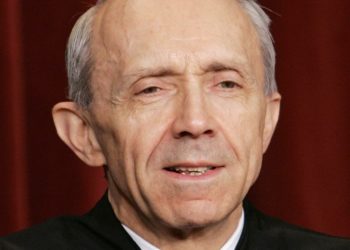

David Souter, former Supreme Court justice and GOP nominee who often sided with liberals, dies

WASHINGTON – Former Supreme Court Associate Justice David Souter, a Republican nominee who sided with his liberal colleagues in many...