‘I Feel a Deep Connection’ to Italian Cinema

Timothée Chalamet underlined the impact of Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me by Your Name” on his career as he received Italy’s...

Solo Traveler Makes Cross-Country Trek with $499 Amtrak Pass, Says It Was the ‘Best Decision’ (Exclusive)

A young woman from Belgium explored the U.S. by train using the Amtrak USA Rail Pass.Her spontaneous choice led to...

Chief Justice John Roberts stresses judicial independence amid tensions with Trump

Chief Justice John Roberts stressed the importance of judicial independence during public remarks Wednesday, noting that the judiciary’s role as...

A man spent 45 days in jail, accused of trying to abduct a child at Walmart. A judge granted a bond after lawyer shows video

Mahendra Patel, who is facing attempted kidnapping and other charges after a mother accused him of trying to grab her...

3 former Memphis officers acquitted in fatal beating of Tyre Nichols after he fled a traffic stop

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (AP) — Three former Memphis officers were acquitted Wednesday of all state charges, including second-degree murder, in the...

Mom speaks out after 8-year-old son orders 70K Dum-Dums on Amazon

A Kentucky mom is speaking out after her 8-year-old son unknowingly ordered 30 boxes of Dum-Dums lollipops on Amazon --...

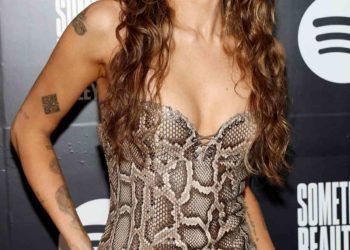

Miley Cyrus’ House Burned Down. Why She Now Sees the Dark Moment as the ‘Biggest Blessing I’ve Ever Had’

Miley Cyrus previewed her upcoming Something Beautiful visual album at an event with Spotify at Metrograph in New York City...

New York town official facing charges after shooting lost DoorDash driver, police say

A New York town official is facing a slew of charges after allegedly shooting a DoorDash delivery driver who was...

Donald Trump taps wellness influencer close to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for surgeon general

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump is tapping Dr. Casey Means, a wellness influencer with close ties to Health and...

Trump to pull surgeon general nominee Janette Nesheiwat

President Donald Trump plans to withdraw his nominee to be surgeon general just one day before Fox News contributor Janette...