‘They’re Very Good at Privacy Here’

Natalie Portman opens up about loving life in Paris with her two childrenThe actress appreciates French manners, privacy and cultural...

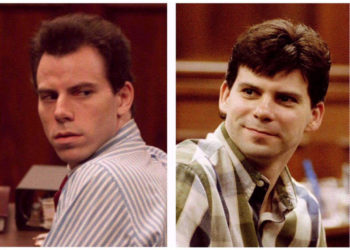

Erik and Lyle Menendez are now eligible for parole after judge resentences them

LOS ANGELES — A California judge on Tuesday resentenced Erik and Lyle Menendez, making the siblings eligible for parole in...

Judge grants re-sentencing bid by Menendez brothers for 1989 shotgun murders

By Lisa RichwineLOS ANGELES (Reuters) - Lyle and Erik Menendez, serving life sentences for the 1989 shotgun murders of their...

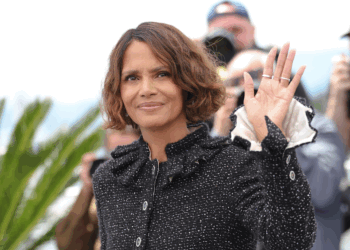

Halle Berry Forced to Change Cannes Dress Amid New Red Carpet Rules, but Says Banning Nudity Is ‘Probably a Good’ Thing

Halle Berry revealed during the Cannes jury press conference that she had to make a last-minute fashion change due to...

Federal grand jury indicts Wisconsin judge in immigration case, allowing charges to continue

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — A federal grand jury indicted a Wisconsin judge Tuesday on charges she helped a man in...

Chuck Schumer says he is placing a hold on Trump DOJ nominees amid questions on Qatar’s luxury jet gift

WASHINGTON — Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said Tuesday he is placing a hold on all Trump Justice Department...

Schumer announces blanket hold on DOJ political nominees as he demands answers on Qatari plane

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer announced Tuesday he is placing a blanket hold on all Justice Department political nominees, as...

Fatal fall in Washington’s North Cascades kills 3, leaves 1 survivor

Three climbers from Renton, Washington died over the weekend after falling during a climb in North Cascades National Park.Personnel from...

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. submerges in creek with high bacteria levels, including E. coli

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. shared photos of himself submerged in Washington, D.C.'s Rock Creek with...

Retirement Is the New Resistance

Earlier this year, Gary Peters made a decision that’s utterly ordinary for most 66-year-olds: He was going to retire. Except...