Trump says Coke agrees to use cane sugar in US

President Donald Trump said Wednesday beverage giant Coca-Cola has agreed to use cane sugar in its iconic drink in the...

Maurene Comey, daughter of James Comey and prosecutor of Jeffrey Epstein, is fired

Maurene Comey, who prosecuted Jeffrey Epstein and is former FBI Director James Comey’s daughter, was fired Wednesday from her job...

Security Experts Are ‘Losing Their Minds’ Over an FAA Proposal

The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas,...

After powerful Israeli strikes on Damascus, Syria withdraws troops from Suwayda city

Israel carried out a series of powerful strikes on the Syrian capital Damascus Wednesday, escalating a campaign it says is...

DHS Secretary Noem says airline carry-on liquids limit could be changed soon

One week after announcing an end to the requirement that passengers remove their shoes when undergoing airport security screening, the...

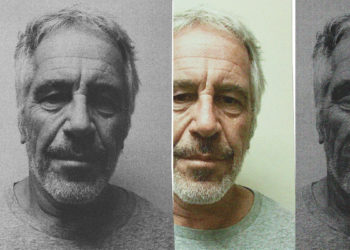

Trump Decries ‘Jeffrey Epstein Hoax,’ and Those Still Raising Issue as ‘Past Supporters’

President Donald Trump answers questions outside the White House in Washington, DC, on July 11, 2025. Credit - Win McNamee—Getty...

How climate crisis makes rainstorms that flooded New York more common

Monday night’s downpour was one of the most intense rainstorms in New York City history, the kind of storm that’s...

Trump, who once fueled conspiracy theories about Jeffrey Epstein, now bears their brunt

President Donald Trump has implored people to stop talking about Jeffrey Epstein. The internet isn’t listening.Trump and many in his...

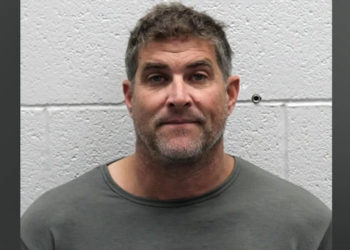

Former MLB player convicted of murder in California home invasion

A former Major League Baseball pitcher has been found guilty of murdering his father-in-law in what prosecutors called a financially...

‘China’s car market has lost all reason’ – the country’s largest western carmaker refuses to compete in Tesla and BYD’s EV price war

Once China’s dominant carmaker before being overtaken by fast-growing EV leader BYD, Volkswagen is now in a rebuilding year. VW...