Deadly New Mexico flash flooding prompts dozens of rescues, sweeps house away

Flash flooding from torrential rain killed at least three people Tuesday afternoon and prompted dozens of rescues in the Ruidoso...

When an American dream turns into a nightmare

Off to camp. It’s an American summer classic. Children get to sleep in cabins and learn to canoe. And parents get...

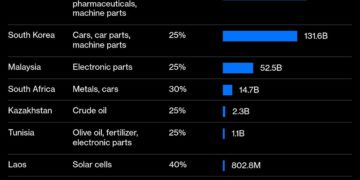

How have prices changed under Trump? Experts explain.

President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs earlier this year set off alarm among economists about a risk that just about every...

Texas officials give few answers to growing questions about response to deadly floods

HUNT, Texas — Four days after the devastating flash floods in Texas Hill Country, local officials and law enforcement in...

Musk chatbot Grok removes posts after complaints of antisemitism

(Reuters) -Grok, the chatbot developed by the Elon Musk-founded company xAI, removed what it called "inappropriate" social media posts on...

Lena Dunham Unpacks Her TV Return ‘Too Much’ and Why It Was Time to Get Personal Again

It’s been seven years since a Lena Dunham show has been on TV, a stretch of time that catches even...

Max Will Change Back to HBO Max on Wednesday

Warner Bros. Discovery has settled on a date to reskin the Max streamer back to HBO Max: Early this Wednesday...

Trump caught off guard by Pentagon’s abrupt move to pause Ukraine weapons deliveries, AP sources say

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump's decision to send more defensive weapons to Ukraine came after he privately expressed frustration...

This new dating trend is leaving people baffled and heartbroken. It’s called ‘Banksying.’

Look out, daters: There's a new toxic relationship trend taking the romantic world by storm.It's called "Banksying," and it derives...

Supreme Court lets Trump pursue mass federal layoffs

By John KruzelWASHINGTON (Reuters) -The U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday cleared the way for Donald Trump's administration to pursue mass...