Trump ally’s Gulf of America bill sparks frustration in House GOP

FIRST ON FOX: A scheduled vote on making President Donald Trump’s Gulf of America name change permanent is causing some...

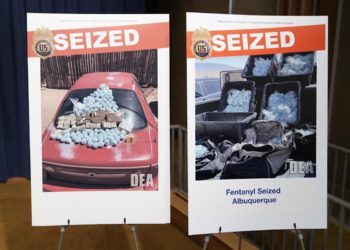

Cartel leader among 16 arrested in historic U.S. fentanyl bust

Sixteen people have been arrested and three million pills laced with fentanyl were seized in what federal prosecutors said Tuesday...

US says it has busted major fentanyl trafficking network

By Sarah N. Lynch and Andrew GoudswardWASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. law enforcement officials said on Tuesday that they had taken...

Trump plans to announce that the US will call the Persian Gulf the Arabian Gulf, officials say

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump plans to announce while on his trip to Saudi Arabia next week that the...

‘Profound, mysterious’ conclave to pick new pope begins: Live updates

Over 130 elector cardinals from around the globe converged Wednesday in Vatican City to vote for the successor to Pope...

Trump announces US to stop bombing Yemen, says Houthis won’t attack more American ships

President Donald Trump made a surprise announcement on Tuesday that the United States would stop bombing the Houthis in Yemen,...

What ‘Conclave’ gets right — and wrong — about papal politics

In the film “Conclave,” now streaming on Prime Video, Ralph Fiennes plays a Catholic cardinal presiding over the election of...

As RFK Jr. pledges food victories, he faces the realities of governing

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took the stage inside his massive health department recently and declared artificial food colorings would soon...

Airport Detentions Have Travelers ‘Freaked Out’

Sign up for Trump’s Return, a newsletter featuring coverage of the second Trump presidency.Jeff Joseph, a 53-year-old immigration attorney in...

India fires missiles across the frontier with Pakistan, killing at least 1 child, officials say

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan (AP) — India fired missiles across the border into Pakistani-controlled territory in at least three locations early Wednesday,...